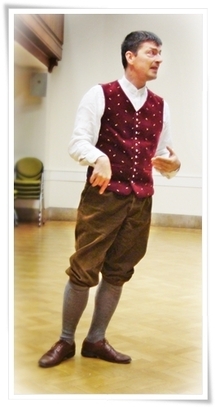

Dr Jed Wentz (c) S. Chaouche

Dr Jed Wentz is internationally known as a virtuoso flutist and also as a conductor. He is the founder of the ensemble ‘Musica ad Rhenum’ which was heard on BBC Radio 3 (‘The Early Music Show’). He completed a PhD entitled “The Relationship between Gesture, Affect and Rhythmic Freedom in the Performance of French Tragic Opera from Lully to Rameau” (Univ. of Leiden). His brilliant work on c18 acting brings a fresh understanding of performance practices during the period. I am delighted to introduce him to our readers.

Could you briefly summarise your activities and career?

I am a flute-player specialized in the performance of 18th-century repertoire on historical instruments; but I have also done some conducting, particularly of ‘Baroque’ opera. About ten years ago I became very interested in 17th- and 18th-century dance, and afterwards became fascinated by the use of gesture in acting on the 18th-century stage. This led to me do my doctorate at Leiden University; my topic was the close relationship between music and gesture in the performance of French opera from Lully to Rameau. I currently teach at the Conservatorium van Amsterdam.

What do you teach at the Conservatorium von Amsterdam?

I teach performance on historical flutes, a class on 17th- and 18th-century musical treatises as well as one on the history of the Early Music movement (of which I am highly critical). I also teach an introductory course to Baroque dance and gesture, and a class on rhetoric.

You are internationally recognized as a flutist virtuoso. Why did you choose to examine operatic and rhetorical gestures?

I have always loved words. To tell the truth, I only like operabecause there is a structured tale being told through music. I just love words: for years I read Racine every evening before I went to sleep. His words are magic, his control of them is astounding, his texts are so compact, so rich, so mellifluous…I have read all his plays over and over again, except for Plaideurs, which makes no sense to me (I am all for tragedy). I have also done my best with Corneille, Voltaire and Crébillon (but there is only one Racine). So it is easy to imagine why French operas, with their tight and carefully written libretti, have a specialappeal. When I realized that the use of gesture would intensify the passions of the words, rather than distracting from them, I became convinced that an historically informed performance of Racine or Quinault would be a riveting experience. My dream is one day to see a very passionate Bajazet, with gestures and facial expressions taken from 17th- and 18th-century paintings, with the alexandrines ‘sung’ in an elevated (but never monotonous) manner, so that the beauty of the words shines out, and with every passion of the text underlined by elegant, violent and/or emotionally charged gestures and facial expressions. But the training it would involve to get the actors to such a point! I fear it will remain a dream…

What were the subjects and findings of your recent works?

The starting point for all of my work is my conviction that the passions were experienced as immediately and as intensely as we experience emotions today…indeed, perhaps even more intensely! The expression of the passions, whether in art, music, dance or theatre, was one of unity rather than of the contrast inherent in the contemporary actor’s so-called ‘counterpoint’: for instance, modern actors may attempt to express deep joy by a dead-pan face, while contemporary stage directors heap layers of unintelligible ‘meaning’ on top of historical librettos or plays (and the more forced and bizarre the director’s ‘counterpoint’ the better they like it, or at least so it seems!).

My current work is to see just how stage works from the 18th-century would function without such ‘counterpoint’. I believethat a unified ‘naturalism’ was central to the expression of the passions, and that some general principles can be drawn from historical rhetorical treatises that apply broadly to the performance arts: each passion has its own tempo in the body, its own inflections in voice and gesture and the change from one passion to another takes time to manifest itself in body and voice. Such a basis for musical and theatrical performance differs radically from current Early Music performance practice ideals, where tempo is steady and expression is modified in order to minimalize interpretation on the part of the performer…that is something an 18th-century audience would have found laughable…after all, what was more highly prized than an actor’s fire?

My current work is to see just how stage works from the 18th-century would function without such ‘counterpoint’. I believethat a unified ‘naturalism’ was central to the expression of the passions, and that some general principles can be drawn from historical rhetorical treatises that apply broadly to the performance arts: each passion has its own tempo in the body, its own inflections in voice and gesture and the change from one passion to another takes time to manifest itself in body and voice. Such a basis for musical and theatrical performance differs radically from current Early Music performance practice ideals, where tempo is steady and expression is modified in order to minimalize interpretation on the part of the performer…that is something an 18th-century audience would have found laughable…after all, what was more highly prized than an actor’s fire?

How do you understand C18 sensitivity and idea of emotion and passion?

To understand the passions we must understand the medical theory of the 17th and 18th centuries, which was inherited from the Ancient Greeks through Galenist texts. We must also accept, as researchers and re-creative performing artists, the validity of concepts like the animal spirits, humors, and the rational and sensitive souls. For instance, I used to speak to my students about how a performer must split his or her consciousness in order to be emotionally involved in the music while still rationally in control of the body: to really be swept away while playing would be disastrous for the performance, would lead to wrong notes and terrible squawks; yet one must project the illusion of complete immersion in affect in order to move the audience. I now explain this in a Galenist context, by contrasting the sensitive soul’s involvement with the passions and sensory perception (heart) to the rational soul’s cool reasoning (brain)...artists must learn to allow the two souls to function simultaneously yet independently. This is a useful metaphor, one that really ‘works’ during performance.

Could you explain how research influenced your practice and understanding of acting in C18?

When I first began working on acting, I thought that the disciplines of music and theatre were very different. In music you create a sound object that is projected away from the performer’s body towards the listener. Actors and dancers, on the contrary, are judged for themselves, their own bodies are on the line: that was a terrifying experience for me at first! But I soon came to see that the musical and theatrical crafts share a common basic need for a flexible sensitive soul, a fiery temperament and a lively imagination: it’s all about strong feeling manifesting itself and being projected outwards, while the performer retains enough ‘distance’in the body in order to perform well and with control.

How did you rehearse and stage the scene by Shakespeare included in Austin’s book?

This was a very long process: I spent a lot of time working on the notation, just trying to understand it, just getting it into the body. Austin uses a system of numbers and letters, dots and dashes which are printed above and below the lines of Shalespeare’s text in order to show where the actor must place his hands and feet, and how he must turn his head and eyes. He also notates if the movements are made broadly or close to the body, gently or with sudden force. All of this needs to be learned mechanically, and carefully and repeatedly checked against the notation to ensure accuracy in performance.

Once I felt reasonably confident that I was moving and standing as Austin’s notation indicated (and of course there is always room for interpretation, so one has to agonize about that and make some educated guesses) I began to compare the gestures in Austin’s version to descriptions of gestures in other rhetorical sources. For instance, there are several gestures in Austin’s notation (published 1806) that can be found in René Bary’s rhetorical works from the 17th century. By comparing various sources for the same gestures I began to see the relationship between text and gesture in a new light. Finally, based on what I understand to be the emotional content of the gestures and by using the force with which Austin asks for them to be performed as a guide to their intensity, I have attempted to ‘passionate’ the speech, to infuse it with logical and ‘natural’ emotions, by making sure each gesture had a specific emotional motivation: rather than being a decorative distraction, I wanted each gesture to mean something emotionally to the character. The struggle with this text has been one of the most rewarding experiences of my performing life.

The result can be seen in the video of the performance I gave during the Oxford symposium Theatre as Visual Spectacle in 2011. It is important to note here, however, that this filmed version is all about the gestures: I have allowed Austin’s gestures to inform the declamation entirely. Sadly, he does not notate anything for the voice; but he does make clear that the violence and height of the gestures should be reflected in the voice.

My current research is about theatrical declamation and the use of the ‘tones’: I hope at some point to return to the ‘Brutus Speech’ and add a more elevated declamation to the gestures…that will get us closer to an 18th-century style performance, I think. The video really is ‘work in progress’.

Once I felt reasonably confident that I was moving and standing as Austin’s notation indicated (and of course there is always room for interpretation, so one has to agonize about that and make some educated guesses) I began to compare the gestures in Austin’s version to descriptions of gestures in other rhetorical sources. For instance, there are several gestures in Austin’s notation (published 1806) that can be found in René Bary’s rhetorical works from the 17th century. By comparing various sources for the same gestures I began to see the relationship between text and gesture in a new light. Finally, based on what I understand to be the emotional content of the gestures and by using the force with which Austin asks for them to be performed as a guide to their intensity, I have attempted to ‘passionate’ the speech, to infuse it with logical and ‘natural’ emotions, by making sure each gesture had a specific emotional motivation: rather than being a decorative distraction, I wanted each gesture to mean something emotionally to the character. The struggle with this text has been one of the most rewarding experiences of my performing life.

The result can be seen in the video of the performance I gave during the Oxford symposium Theatre as Visual Spectacle in 2011. It is important to note here, however, that this filmed version is all about the gestures: I have allowed Austin’s gestures to inform the declamation entirely. Sadly, he does not notate anything for the voice; but he does make clear that the violence and height of the gestures should be reflected in the voice.

My current research is about theatrical declamation and the use of the ‘tones’: I hope at some point to return to the ‘Brutus Speech’ and add a more elevated declamation to the gestures…that will get us closer to an 18th-century style performance, I think. The video really is ‘work in progress’.

What type of workshops did you organize?

I have given many workshops at universities and conservatories for early musicians, theatre students, English majors and singers. I demonstrate the use of gesture and how it can transform our understanding of texts and their meaning through performance…I am always surprised how responsive young people are to this old-fashioned style of acting!

What would you advise to a company aiming to stage a C18 French play or opera?

I think it is essential that a production have enough time to prepare properly, which is almost never the case. Take plenty of time: nothing can look natural until it is in the body, and before that we cannot speak of acting; moving from one constrained pose to another (without inner fire or an understanding of the passionate motivation of the character) is not acting and is in fact an insult to the complex technique 17th- and 18th-century actors must have had (for which I have much respect).

What is your position concerning contemporary “baroque” acting and staging?

We fall far short of their standards for emotional projection. But then we are so much more witty in our post-modern irony!

What are your new projects?

Having worked on gesture I am now looking to declamation. What a can of worms waits to be opened there! I also hope to work on a few scenes just to challenge myself: the title role in Southerne’s Oroonoko, and Agamemnon in Racine’s unjustly neglected Iphigénie.

Chinese Portrait

If you were:

A rhetorical gesture:

Weight forward on the left leg, right leg with knee bent and toe touching the ground: the left elbow slightly bent, left hand just above hip-level, left palm parallel to the floor. Right hand (with index finger pointing heavenwards) curved back behind the right ear. Nose pointed towards the left, eyes looking right…well, you did ask!

An opera:

Mozart, La Clemenza di Tito.

A musical piece:

I’d love to say that I am like Bach’s Musical Offering, but I fear I’m more like Yamkee Doodle.

A treatise on acting:

The final version of Aaron Hill’s Essay, it’s all about the manifestations of the passions in the face and eyes..

A dance:

Any one of a number of Irish Set Dances…Set dancing is absolute heaven, something in which to lose one’s self…though I also love Scotland, and Strip the Willow danced at a Highland ceilidh in my kilt comes a close second.

A passion/emotion:

Oh, one must never get stuck in any one passion for more than a few moments! They must always be changing.

A C18 actor:

Not Garrick! He must have been a dreadful ham. Thomas Betterton, perhaps?

A playhouse:

The Comédie-Française, for sure.

A C18 costume:

I have seen some very nice costume designs for sea monsters, with bat’s wings, webbed feet and huge claws. That’s something for me.

A musical note:

‘Ut’: the rhetorical text I am working on now centers on ‘ut’ and it’s use in theatrical declamation. I am fascinated by the idea that actors used pitches (‘tones’) to recite and that choosing the proper‘tone’ for each passage was an essential part of their declamatory craft. There are some interesting anecdotes in Dutch sources about this…it seems that music and words came together on more stages than just the operatic one.

A composer:

Telemann. If I could meet one composer from the 18th century it would be Telemann, such a witty, intelligent and knowledgeable man! And, he loved French music too.

Interview by Sabine Chaouche

A rhetorical gesture:

Weight forward on the left leg, right leg with knee bent and toe touching the ground: the left elbow slightly bent, left hand just above hip-level, left palm parallel to the floor. Right hand (with index finger pointing heavenwards) curved back behind the right ear. Nose pointed towards the left, eyes looking right…well, you did ask!

An opera:

Mozart, La Clemenza di Tito.

A musical piece:

I’d love to say that I am like Bach’s Musical Offering, but I fear I’m more like Yamkee Doodle.

A treatise on acting:

The final version of Aaron Hill’s Essay, it’s all about the manifestations of the passions in the face and eyes..

A dance:

Any one of a number of Irish Set Dances…Set dancing is absolute heaven, something in which to lose one’s self…though I also love Scotland, and Strip the Willow danced at a Highland ceilidh in my kilt comes a close second.

A passion/emotion:

Oh, one must never get stuck in any one passion for more than a few moments! They must always be changing.

A C18 actor:

Not Garrick! He must have been a dreadful ham. Thomas Betterton, perhaps?

A playhouse:

The Comédie-Française, for sure.

A C18 costume:

I have seen some very nice costume designs for sea monsters, with bat’s wings, webbed feet and huge claws. That’s something for me.

A musical note:

‘Ut’: the rhetorical text I am working on now centers on ‘ut’ and it’s use in theatrical declamation. I am fascinated by the idea that actors used pitches (‘tones’) to recite and that choosing the proper‘tone’ for each passage was an essential part of their declamatory craft. There are some interesting anecdotes in Dutch sources about this…it seems that music and words came together on more stages than just the operatic one.

A composer:

Telemann. If I could meet one composer from the 18th century it would be Telemann, such a witty, intelligent and knowledgeable man! And, he loved French music too.

Interview by Sabine Chaouche

Bibliography

for a complete list of publications please visit: [http://jedwentz.com]

Full CV

Articles:

- ‘Sonority in the 18th Century: un poco più forte?’, in Early Music, vol. XXII, issue 3 (August: 1994), 413-496. Co-written by Willem Kroesbergen.

- ‘The Passions Dissected, or, on the dangers of boiling down Alexander the Great’, in Early Music, vol. 37, issue 1 (2009), 101-112.

- ‘Gaps, Pauses and Expressive Arms: Reconstructing the Link between Stage Gesture and musical Timing at the Académie Royale de Musique’, in Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 32, no. 4 (December, 2009), 607-623.

- ‘Deformity, delight and Dutch dancing dwarfs: An 18th-century suite of prints from the United Provinces’, in Music and Art, Vol. XXXVI (2010).

- ‘Roxana’s Dance: e Persuasive Footwork of Defoe’s Fortunate Mistress’, in The 18th- century Novel, vol. 8 (October 2011), 61-118.

- ‘Les enfans du Sr. Frederic: the identities and performances of a theatre family active in the United Provinces, 1759-1763’ with Anna de Haas, forthcoming in The Dutchman and the Honeybees: dance, diaspora and the Dutch Republic

Book Publication:

- Jed Wentz, ed., The Dutchman and the Honeybees: dance, diaspora and the Dutch Republic (Conservatorium van Amsterdam, forthcoming).

- Jed Wentz, trans. and ed., Jacques Martin Hotteterre, L’Art de préluder (forthcoming: Edition Walhall).

Conferences Organized (papers presented):

- The Dutchman and the Honeybees: An International Baroque Dance Symposium (Amsterdam: Conservatorium van Amsterdam: 2009). Paper given together with Baroque dancer and dance historian Jennifer Thorp, New College, Oxford: ‘Eyes, Feet, Ears and Hearts: Baroque Dance in Experimental Times’.

- Gesture on the French Stage, 1675-1800 (Utrecht: Utrecht Early Music Festival: 2010). Paper given: ‘Affect, Gesture and Rubato at the Opéra’.

Conferences Attended (papers presented):

1994

- Conference: Le Mouvement en Musique à l’Époque Baroque, Metz. Paper: ‘Les Indications de Tempo de J. S. Bach à Lumière de Die Kunst des reinen Satzes de J. Ph. Kirnberger’.

2006

- Conference: Music and Gesture II (Manchester: Royal Northern College of Music). Paper

2008

- Conference of the Society for Seventeenth-Century Music (Pasadena, California: Hungtington Library). Paper given: ‘Roxana’s Dance: the Persuasive Footwork of Defoe’s Fortunate Mistress’. Awarded the Irene Alm Memorial Prize.

- Conference: Dance, Timing and Musical Gesture (Edinburgh: Institute for Music in Human and Social Development, Edinburgh University). Paper given: ‘Eyes, Feet, Ears and Hearts: Baroque Dance in Experimental Times’. Given together with Baroque dancer and dance historian Jennifer Thorp, (New College, Oxford).

- Conference of the British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies (Oxford: St. Hugh’s College). Paper given: ‘Roxana’s Dance: The Persuasive Footwork of Defoe’s Fortunate Mistress’. Given in a session on the novels of Defoe.

2009

- International Conference on Music and Emotion (Durham: University of Durham).

Paper given: ‘Grimarest’s Prescription’.

2010

- Conference of the British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies (Oxford: St. Hugh’s College). Workshop given: ‘And Leaves the World to Darkness and to Me’. A workshop on Gilbert Austin’s notational system for gesture.

- Conference: Dance and Image (Oxford: New College, Oxford Dance Symposium)

‘Lifting the Mask of Mlle. Horibilicribrifaxin’.

2011

- Conference: American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies (Vancouver, Canada).

Participation/performance: Roundtable ‘Reading /Reciting Eighteenth-Century English’.

Performance: ‘Brutus’ Speech from Julius Caesar as notated by Gilbert Austin’.

- Cesar Seminar: Theatre as Visual Spectacle (Oxford: Taylor Institution Library).

Paper: ‘Reconstructing Gesture for French Baroque Opera: some pitfalls and points of departure’.

- Conference: Dance and the Novel (Oxford: New College, Oxford Dance Symposium).

Paper/workshop: ‘An Impostor Princess and a Royal Fool: reconstructing Defoe’s mismatched masquerade courante’.

- Colloque et ateliers: Le Tableau et la Scène: Peinture et mise en scène du répertoire héroique dans la première moitié du XVIIIe siècle (Nantes: Musée des Beaux-arts de Nantes). Workshop: ‘Une scène à patir de l’apport de l’œuvre des Coypel: le monologue d’Armide’.

- Conference on historical staging (Drottningholm, Sweden, on invitation of Mark Tatlow).

Causerie to initiate roundtable discussion: ‘The Place of Gesture in Contemporary Opera

Productions: some pros and cons’.

2012

- Conference of the British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies

(Oxford: St. Hugh’s College). Paper given: ‘Speech as soundscape: the space between the

notes in Joshua Steele’s Prosodia Rationalis’.

2011 Workshop

- Workshop (University of Winchester). Lecture/demonstration: ‘Meaning in Movement: historical acting as textual analysis’.

- Workshop (Anton Bruckner Privatuniversität, Linz). Lecture/demonstration: ‘French Rhetorical Sources and the Expression of the Passions’.

- Workshop (Longy School of Music) ‘17th- & 18th-century French Rhetorical Texts’.

- Workshop (Conservatorium van Amsterdam) ‘Gesture in French recitatives: a workshop for for singers’.

Full CV

Articles:

- ‘Sonority in the 18th Century: un poco più forte?’, in Early Music, vol. XXII, issue 3 (August: 1994), 413-496. Co-written by Willem Kroesbergen.

- ‘The Passions Dissected, or, on the dangers of boiling down Alexander the Great’, in Early Music, vol. 37, issue 1 (2009), 101-112.

- ‘Gaps, Pauses and Expressive Arms: Reconstructing the Link between Stage Gesture and musical Timing at the Académie Royale de Musique’, in Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, vol. 32, no. 4 (December, 2009), 607-623.

- ‘Deformity, delight and Dutch dancing dwarfs: An 18th-century suite of prints from the United Provinces’, in Music and Art, Vol. XXXVI (2010).

- ‘Roxana’s Dance: e Persuasive Footwork of Defoe’s Fortunate Mistress’, in The 18th- century Novel, vol. 8 (October 2011), 61-118.

- ‘Les enfans du Sr. Frederic: the identities and performances of a theatre family active in the United Provinces, 1759-1763’ with Anna de Haas, forthcoming in The Dutchman and the Honeybees: dance, diaspora and the Dutch Republic

Book Publication:

- Jed Wentz, ed., The Dutchman and the Honeybees: dance, diaspora and the Dutch Republic (Conservatorium van Amsterdam, forthcoming).

- Jed Wentz, trans. and ed., Jacques Martin Hotteterre, L’Art de préluder (forthcoming: Edition Walhall).

Conferences Organized (papers presented):

- The Dutchman and the Honeybees: An International Baroque Dance Symposium (Amsterdam: Conservatorium van Amsterdam: 2009). Paper given together with Baroque dancer and dance historian Jennifer Thorp, New College, Oxford: ‘Eyes, Feet, Ears and Hearts: Baroque Dance in Experimental Times’.

- Gesture on the French Stage, 1675-1800 (Utrecht: Utrecht Early Music Festival: 2010). Paper given: ‘Affect, Gesture and Rubato at the Opéra’.

Conferences Attended (papers presented):

1994

- Conference: Le Mouvement en Musique à l’Époque Baroque, Metz. Paper: ‘Les Indications de Tempo de J. S. Bach à Lumière de Die Kunst des reinen Satzes de J. Ph. Kirnberger’.

2006

- Conference: Music and Gesture II (Manchester: Royal Northern College of Music). Paper

2008

- Conference of the Society for Seventeenth-Century Music (Pasadena, California: Hungtington Library). Paper given: ‘Roxana’s Dance: the Persuasive Footwork of Defoe’s Fortunate Mistress’. Awarded the Irene Alm Memorial Prize.

- Conference: Dance, Timing and Musical Gesture (Edinburgh: Institute for Music in Human and Social Development, Edinburgh University). Paper given: ‘Eyes, Feet, Ears and Hearts: Baroque Dance in Experimental Times’. Given together with Baroque dancer and dance historian Jennifer Thorp, (New College, Oxford).

- Conference of the British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies (Oxford: St. Hugh’s College). Paper given: ‘Roxana’s Dance: The Persuasive Footwork of Defoe’s Fortunate Mistress’. Given in a session on the novels of Defoe.

2009

- International Conference on Music and Emotion (Durham: University of Durham).

Paper given: ‘Grimarest’s Prescription’.

2010

- Conference of the British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies (Oxford: St. Hugh’s College). Workshop given: ‘And Leaves the World to Darkness and to Me’. A workshop on Gilbert Austin’s notational system for gesture.

- Conference: Dance and Image (Oxford: New College, Oxford Dance Symposium)

‘Lifting the Mask of Mlle. Horibilicribrifaxin’.

2011

- Conference: American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies (Vancouver, Canada).

Participation/performance: Roundtable ‘Reading /Reciting Eighteenth-Century English’.

Performance: ‘Brutus’ Speech from Julius Caesar as notated by Gilbert Austin’.

- Cesar Seminar: Theatre as Visual Spectacle (Oxford: Taylor Institution Library).

Paper: ‘Reconstructing Gesture for French Baroque Opera: some pitfalls and points of departure’.

- Conference: Dance and the Novel (Oxford: New College, Oxford Dance Symposium).

Paper/workshop: ‘An Impostor Princess and a Royal Fool: reconstructing Defoe’s mismatched masquerade courante’.

- Colloque et ateliers: Le Tableau et la Scène: Peinture et mise en scène du répertoire héroique dans la première moitié du XVIIIe siècle (Nantes: Musée des Beaux-arts de Nantes). Workshop: ‘Une scène à patir de l’apport de l’œuvre des Coypel: le monologue d’Armide’.

- Conference on historical staging (Drottningholm, Sweden, on invitation of Mark Tatlow).

Causerie to initiate roundtable discussion: ‘The Place of Gesture in Contemporary Opera

Productions: some pros and cons’.

2012

- Conference of the British Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies

(Oxford: St. Hugh’s College). Paper given: ‘Speech as soundscape: the space between the

notes in Joshua Steele’s Prosodia Rationalis’.

2011 Workshop

- Workshop (University of Winchester). Lecture/demonstration: ‘Meaning in Movement: historical acting as textual analysis’.

- Workshop (Anton Bruckner Privatuniversität, Linz). Lecture/demonstration: ‘French Rhetorical Sources and the Expression of the Passions’.

- Workshop (Longy School of Music) ‘17th- & 18th-century French Rhetorical Texts’.

- Workshop (Conservatorium van Amsterdam) ‘Gesture in French recitatives: a workshop for for singers’.

Awards

Awards for CDs recordings:

International Cini Prize, Venice, awarded to: Vivaldi, Alla Rustica, Fidelio Classics #9217.

International Cini Prize, Venice, awarded to: Locatelli, Sonatas op. 2, Vanguard Classics

#99098/99.

Diapason d’Or, awarded to: J. S. Bach, Complete Chamber Music for Flute.

Awards for academic papers:

Irene Alm Memorial Prize, awarded by the Society for Seventeenth-Century Music to:

‘Roxana’s Dance: e Persuasive Footwork of Defoe’s Fortunate Mistress’.

International Cini Prize, Venice, awarded to: Vivaldi, Alla Rustica, Fidelio Classics #9217.

International Cini Prize, Venice, awarded to: Locatelli, Sonatas op. 2, Vanguard Classics

#99098/99.

Diapason d’Or, awarded to: J. S. Bach, Complete Chamber Music for Flute.

Awards for academic papers:

Irene Alm Memorial Prize, awarded by the Society for Seventeenth-Century Music to:

‘Roxana’s Dance: e Persuasive Footwork of Defoe’s Fortunate Mistress’.

Musica Ad Rhenum

In 1992 Jed founded Musica ad Rhenum, with whom he has recorded more than 20 CDs both as flutist and conductor. His recording of the complete flute sonatas of Locatelli was awarded the prize for the Best Recording of Italian Music 1995 by the Fondazione Cini Venetia. Dr. Wentz teaches at the Amsterdam Conservatory of Music, and lectures regularly on performance practice at the Royal Academy of Music in London. He has published articles in Early Music, Concerto, and Tijdschrijft voor Oude Muziek.

Discography:

Musica Ad Rhenum

audio

Discography:

Musica Ad Rhenum

audio